In 2023, artificial intelligence was the focus of many discussions concerning authorship and ownership, the future of labour, copyright, ethics, shifting legalese and expanding concepts of open culture. You can read about the ways Creative Commons has been supporting these important conversations here, here and here.

But I don’t want to talk about any of that today.

Today, I just want us to consider datasets. How datasets frame the way we understand ourselves through visual records. What’s in a dataset, how we retrieve the information within them, and why it matters what stories they convey and omit.

I am a collage artist and remixer of audio visual things. I am also an educator engaging young people in media literacy and critical thinking through creative expression. This learning is facilitated through engaging with the cultural commons, contributing CC0 licensed works to the public domain, remixing and creating meaning with found materials.

Our process begins with search. WHAT we find, WHERE we find it and HOW we find it frames the meaning found in the works we create.

Accessing the cultural commons contained in archives is becoming increasingly opaque as information retrieval practices of “search and find” (search engines) are replaced with “asked and answered” (AI), constricting our view of the larger context, pacifying our curiosity and limiting our imaginations.

When I use the terms US, WE and OURSELVES, I mean an ideal WE, one that includes all the WEs. It’s hard to imagine such a complete dataset. No such record of the entirety of our we- ness currently exists. The cultural commons is an idea as ever changing as culture itself. And therein lies the (growing) problem.

We are training AI systems to understand us based on wildly incomplete reflections of our reality. Then feeding those incomplete snapshots back into the training system, eliminating divergence of thought and flattening culture.

Finding Ourselves

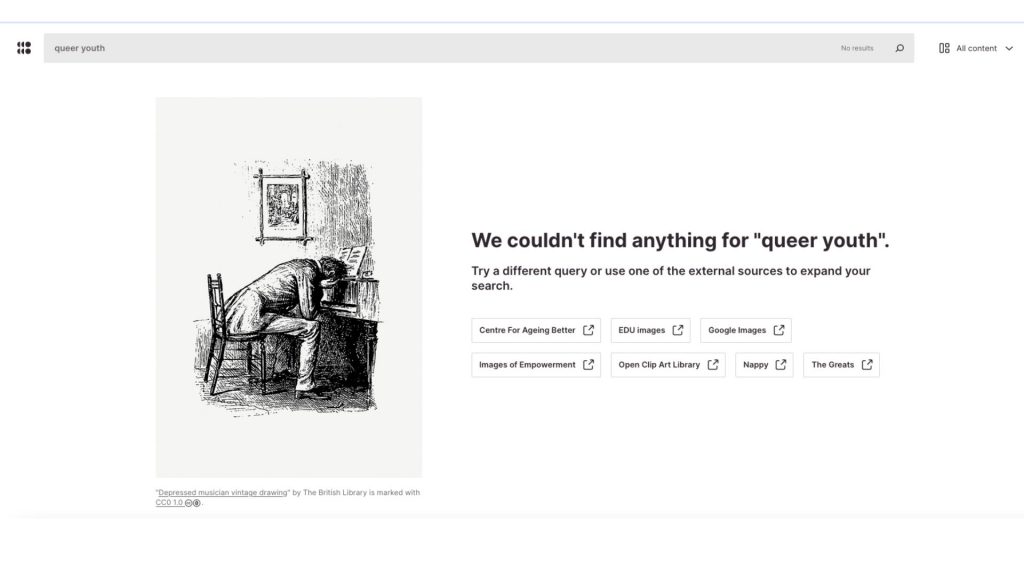

When we begin online search and find missions, we quickly learn how many of “our” stories are missing from the visual record.The current state of image archives, accessible through platforms ranging from Getty Images to Wikimedia Commons, reveals significant omissions in representation.

Enter generative AI. Purporting to be the solution to all our search and find problems. Can’t find an image of “aerial view of forest fire from a plane” in stock image libraries? AI can make it for you!

But what if I am looking for an image of youth as diverse as the ones living in Scarborough, Ontario for outreach materials that reflect those being engaged in an after school program?

While generative AI can create images based on words associated with media files within its datasets, it can NOT understand concepts. Any impression that it is conceptualizing is merely projective anthropomorphism, reflective of our profound relationship with communication.

AI systems recognize patterns and autofill sequential assumptions. A more complex version of fill-in-the-blanks:

cat, kitten,

dog,…puppy

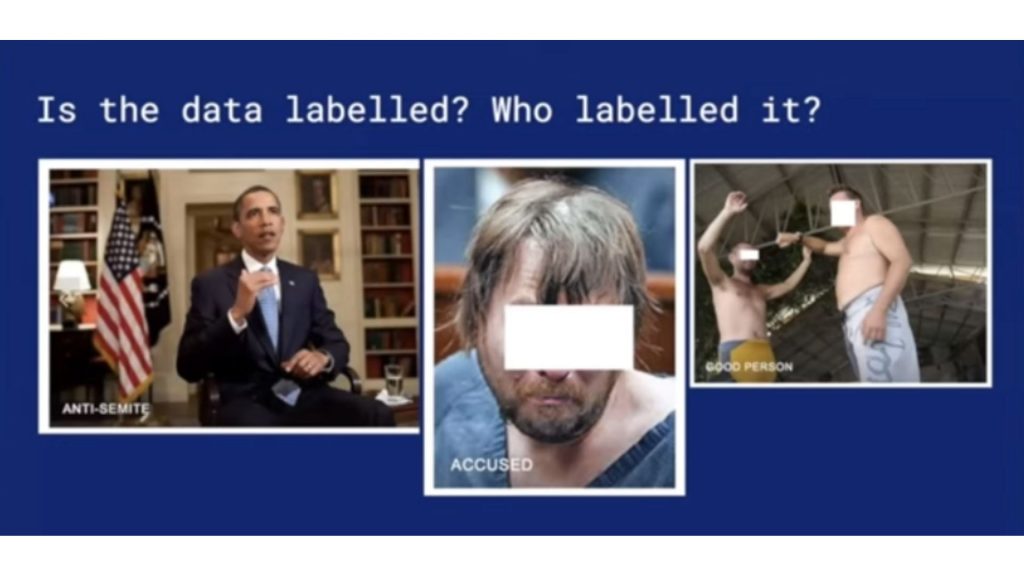

AI systems value quantity, having no way to analyze quality. The reality of online datasets heavily weighted towards representations OF women rather than BY women (from Mona Lisa to Pornhub) means there is a lot of metadata that tags the word #beautiful with such representations, resulting in observable associations AI generates in outputs. We humans know men can be beautiful and that beauty is a completely subjective term, but what our data teaches the AI is that beauty is a descriptor for the female object. Just one of many examples of how AI amplifies existing bias in datasets.

The current state of the visual commons accessed through online search, as well as archives and collections of libraries and museums are rife with over and under-represented cultural understandings of race, gender, beauty norms, family structures, power systems, good taste, knowledge keepers, politics, on and on.

Critical thinking skills can help us to understand what media found in datasets reflect about society. But not if we can’t see them.

Because these AI platforms are run by media corporations concerned with their reputations, a public relations fuelled course-correction is being implemented to manipulate outcomes to be more pleasing and less reflective of the inadequacies of datasets they are trained on. What’s more, because each new version of these software replaces the previous version, observing these changes is reserved to early adopters.

Can’t find an image of young Black men that don’t reflect stereotypes? Generative-AI can produce those too! But should they?

This tweaking of outputs is a type of synthetic DEI (diversity, equity and inclusion), astroturfing over the social biases and media-information structures reflected by the gaps. It trains the AI to generate a surface representation of identities by mashing up concepts, understood through metadata/tags associated with images in its datasets.

Besides creating some pretty strange outputs, this synthetic source material robs communities of the opportunity for self representation.

Nothing about us without us.

When these performative outputs are then reintegrated into datasets, the distortion of reality affects the record of our past, present and future, robbing us all of a record of social change.

Knowing Ourselves

The datasets that train Large Language Models, determining the outputs of generative AI, are records of our past. Despite the misguided description of these outputs as novel, they are just the opposite. These records of our past are already limited by the many biases baked into systems governing how these records are indexed and ordered. SEO rankings are determined by commercial investment, colonial systems outline the terms of the dewey decimal system, elitist gatekeepers determine what works of art are in “the canon”.

AI systems ranging from data-mining, algorithmic recommendations, chatbots and generative media, compound these issues.

Netflix’s algorithm recommends something similar to what you liked before and inevitably you are cornered into a niche of yesterday’s imagination, endlessly consuming increasingly narrow interpretations of what you liked last year.

As Jacob Ward outlines in his book “The Loop : How Technology is Creating a World Without Choices and How to Fight Back”, by pulling from records of our past, we compound these limited understanding of ourselves, tightening the loop between input and output, further limiting diversity of expression.

Expressing ourselves

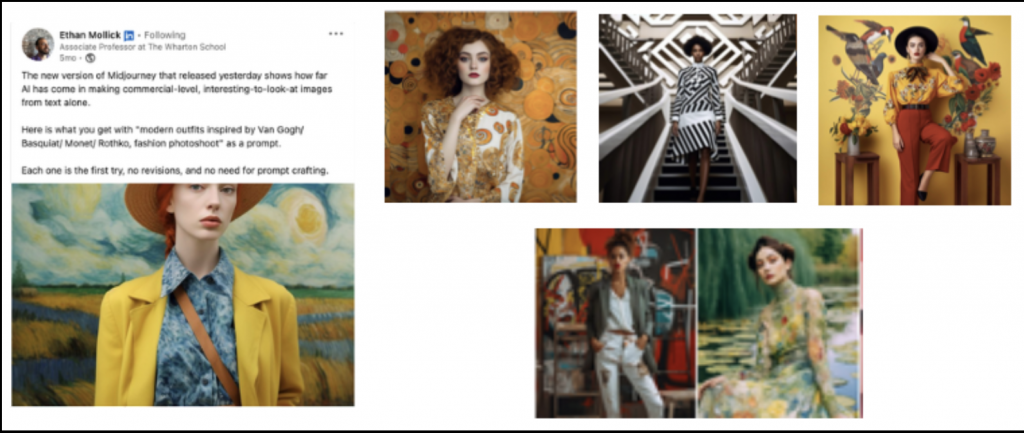

Art and culture are expressions of meaning. An artist’s body of work is a lexicon of its own. Generative AI swallows these languages whole and spits them out as a subheading, reducing their meaning to an aesthetic, a pattern, a colour-pallet, a motif.

Frida Khalo = jungle motif

Escher = monochromatic asymmetry

Basquiat = ripped jeans

This is a threat to our understanding of the meaning contained within the visual commons and the cultural contributions of past creators. “In the style of” (Picasso) prompts can not be replaced with “in the spirit of”, or “containing similar meaning to” as AI systems have no frame of reference for interpreting such sentiments.

Distillation becomes distortion.

These issues are not new to media environments. 75% of people will never scroll past the first page on a Google search. Front page news and cover girls have always pulled focus from the icebergs of information under the surface. But as AI comes to dominate search, and overwhelming indexes (TLDR culture) become replaced with one answer from automated oracles, we move farther away from context, acknowledgement and the ability to see things differently.

Deciding for ourselves

After reading this, you might imagine I am against the use of generative AI. I am not. But I am concerned about how AI is transforming our cultural commons, filling gaps in representation with synthetic realities faster than we can address these gaps ourselves. Shortcuts do lip-service to social change. Rewriting the past removes the chance to learn about ourselves.

When I think about CC0 and public domain archives as the art materials of the remixer, I would hope to see a continued commitment to expanding the digitized record of our cultural commons, but instead see AI’s role in contracting that pool of resources, restricting the dataset available to meaning-makers and offering stereotypical-tripe in its place.

I am happy that we are past the peak AI hype cycle after its explosive entrance into the mainstream in 2023. I am just getting started in experimenting with the technology myself, and I hope you join me/those of us who are.

The noise is dying down and it’s time to get to work. It’s not a question of if but rather how AI systems will transform society and the commons. We need diversity of critique as well as imagination in order to do this.